Why Lasting Sino-India Ties Require Political Change in China

Sustained improvement in Sino-India ties is highly unlikely until there is a fundamental political change in China. This is not merely the result of unresolved border disputes or periodic flare-ups, but due to deeper structural and ideological contradictions between the two countries.

- China’s Political System and Nationalism

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s legitimacy is tied to nationalism and the projection of strength. Since the global financial crisis of 2008, Beijing has increasingly positioned itself as a challenger to Western dominance. India, as a large, democratic, and rising power, inevitably becomes a rival in this narrative. Border tensions, technology restrictions, and economic friction are not accidental—they flow from a system that needs to show dominance to its people. So long as this remains the CCP’s governing principle, concessions to India will remain politically unviable.

- Territorial Disputes and Power Hierarchies

China’s claims over Arunachal Pradesh and its aggressive posture along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) go beyond geography. They are about power and hierarchy. Acknowledging India’s position would mean accepting strategic parity, something Beijing has resisted consistently. Even after decades of agreements, like the 1993 and 1996 confidence-building measures, China has repeatedly undermined them when it suits its strategic objectives. This use of border disputes as political tools makes lasting reconciliation extremely difficult.

- Ideological Contradictions: Democracy vs. Authoritarianism

India’s democratic system presents an alternative model of governance in Asia, one that directly challenges China’s claim that authoritarian control is superior for development. For the CCP, granting India equal recognition would dilute its narrative of one-party supremacy. This ideological contradiction is an underappreciated driver of mistrust, but it ensures that the rivalry is not just material but also systemic.

- China’s Global Strategy and India’s Alignment

China’s rise is tied to initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which India has rejected on sovereignty grounds in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. India’s growing partnerships with the United States, Japan, Australia, and Europe, through platforms like the Quad, further entrench rivalry. For Beijing, India’s strategic autonomy is not accepted as a sovereign choice but is viewed as part of a containment strategy. This makes cooperation inherently fragile.

- The Role of Political Change in China

Only a fundamental shift in China’s internal politics away from one-party authoritarianism and towards a more cooperative governance model could change this trajectory. Until then, engagement will remain limited to compartmentalised areas, such as trade and climate negotiations, while mistrust dominates strategic affairs.

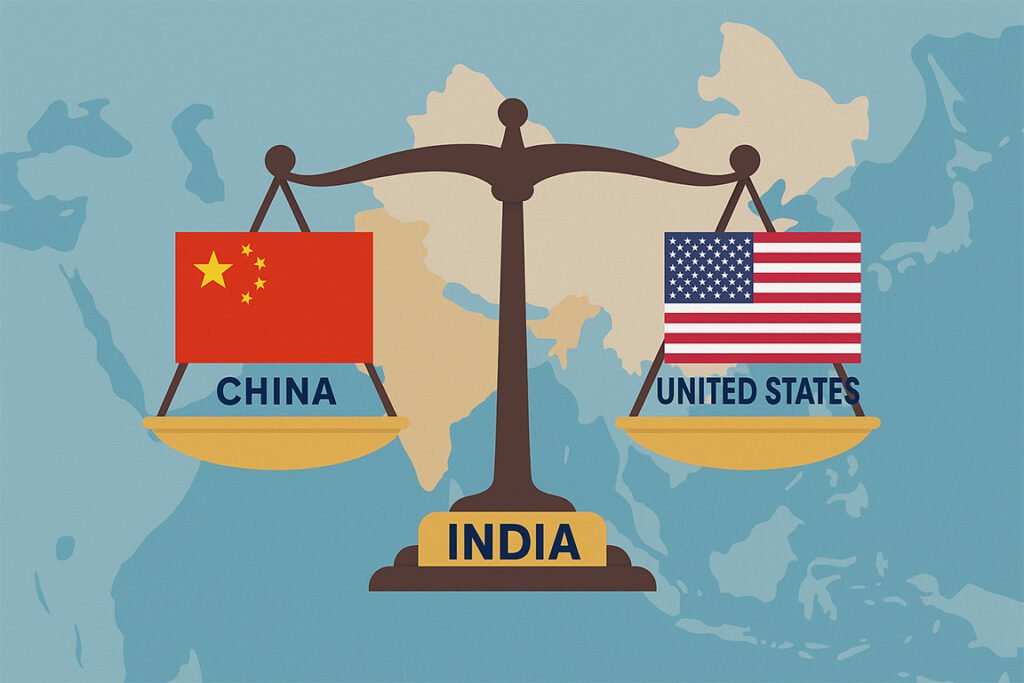

Using China and the United States as Counterbalances

While structural improvement in ties with China is improbable, India need not view its choices as binary. A more pragmatic path is to use both China and the United States as counterbalances, preventing overdependence on either side.

India can leverage China’s economic weight without compromising sovereignty. Despite security concerns, trade between India and China remains significant, particularly in intermediate goods, electronics, and pharmaceuticals. By carefully managing this economic interdependence, New Delhi can reduce vulnerabilities while still benefiting from China’s manufacturing depth. At the same time, India can signal to Washington that it retains room for manoeuvre, thereby avoiding becoming a passive junior partner in the US-led order.

India’s partnership with the United States provides strategic depth, technology access, and defense cooperation that balances Chinese assertiveness. Initiatives like iCET (Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technologies) and defense exercises deepen India-US ties. Yet, by occasionally engaging China in forums such as BRICS, SCO, or RIC (Russia-India-China), India ensures that Beijing cannot dismiss New Delhi as merely an extension of Washington’s strategy. This dual approach strengthens India’s bargaining power on both sides.

Finally, India can use this balancing act to reinforce its doctrine of strategic autonomy. By extracting technology and capital from the United States while keeping selective trade and multilateral cooperation with China alive, New Delhi maximizes its options. In a multipolar world, this balancing strategy ensures India is not locked into a rigid alliance system but remains a pole in its own right.

Conclusion

The structural contradictions between India and China—rooted in authoritarian nationalism, border coercion, and ideological rivalry—make sustained improvement in ties unlikely until Beijing undergoes fundamental political change. But India need not wait passively. By smartly balancing relations with both China and the United States, New Delhi can protect its sovereignty, enhance its options, and ensure that its rise remains insulated from great-power rivalry.