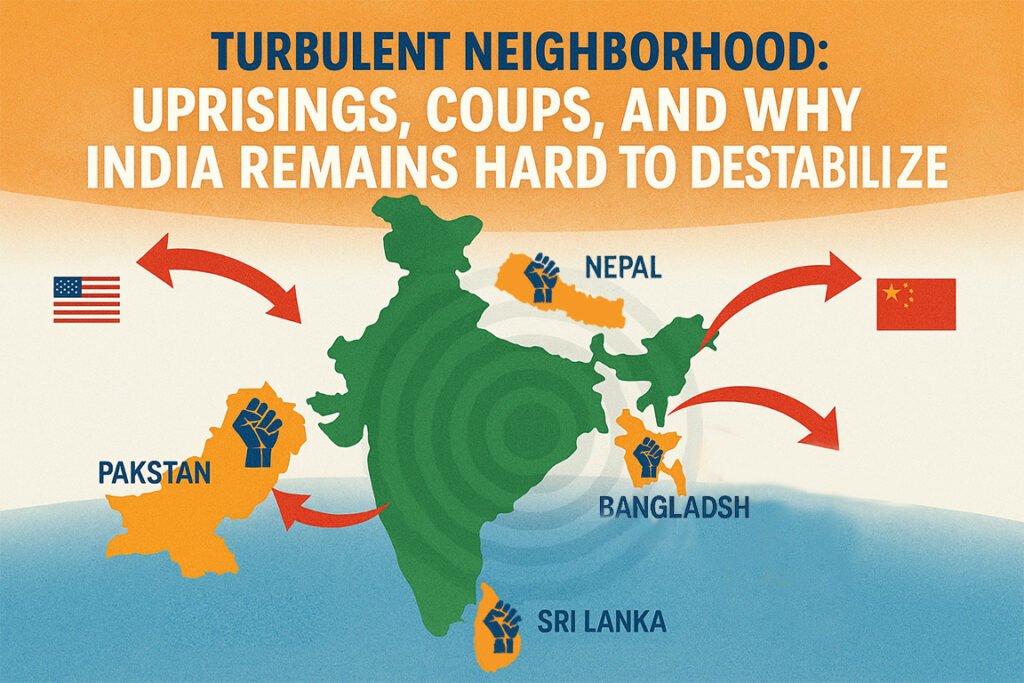

Turbulent Neighborhood: Uprisings, Coups, and Why India Remains Hard to Destabilize

Introduction

South Asia’s political weather has been stormy. Sri Lanka’s 2022 mass uprising over fuel and food shortages toppled a president; Pakistan has lurched through cycles of elite confrontation, street protest, and military tutelage; Bangladesh has seen recurring unrest and hard-edged political rivalry; Nepal rotates coalitions and constitutions with dizzying speed. Commentators often ask whether such shocks are “made in South Asia” or nudged by outside powers. The sober answer is: domestic conditions create the tinder; external actors sometimes add sparks but they rarely control the fire.

This essay (1) maps the core domestic drivers of instability in India’s neighborhood; (2) explains the toolkit of external influence commonly alleged to originating from the U.S. and its intelligence community, as well as China’s political-economic leverage; (3) places those allegations in historical perspective with examples from other regions where covert action is documented; and (4) explains why India, despite being a target of competing narratives and influence operations, has been structurally resilient and is unlikely to face successful externally driven regime change.

I. The neighbourhood: snapshots of instability

Sri Lanka (2022)

A textbook case of domestic macroeconomic mismanagement: tax cuts that hollowed revenue, an ill-timed fertiliser ban that hit agriculture, a terms-of-trade shock in imported fuel, and dwindling foreign exchange. When queues formed and prices spiked, cross-class mobilisation followed. Foreign actors were blamed in some quarters, but the proximate causes were local: twin deficits, policy errors, and a fragile balance of payments.

Pakistan

Instability is structural: a civil–military imbalance, narrow tax base, recurring IMF programs, and polarized politics. “Hybrid” arrangements repeatedly break down, producing cycles of brinkmanship, arrests, and street protests. Outside powers have influence—through aid, arms, or diplomacy—but the decisive variable remains Rawalpindi’s civil–military equation and Pakistan’s own economic weaknesses.

Bangladesh

Rapid growth coexists with winner-take-all politics. Allegations of electoral manipulation, opposition crackdowns, and shrinking space for dissent have produced periodic protest waves. Western governments criticised the lack of transparency in the trial and sentencing of members of Jamat-e-Islami for their alleged involvement in the 1971 genocide conducted by the Pakistani Army in then East Pakistan; Jamat-e-Islami, as a hardline Islamic organisation present across multiple countries with millions of members has been an opponent of secular forces of Bangladesh, right from when it became independent from Pakistan in 1971. China finances infrastructure; India anchors connectivity and security. While Bangladesh saw some growth, it was centred purely around the export of textiles, and COVID exposed the country’s economic fragility. Government actions against political opponents raised questions on the government’s legitimacy and abuse of law and order machinery. Economic pressures (jobs, prices, inequality) from COVID-19 eroded people’s trust in government. All these factors explain most of the volatility.

Nepal

Coalition churn reflects fractured party systems, creating a revolving door of unstable governments. Constitutional experimentation eroded people’s trust in the legitimacy of the system. External players court Kathmandu, but governments mainly fall because of internal factionalism and unstable arithmetic in parliament. Nepal’s GDP growth rate has hovered around 4.5% in FY25, which for a country with a low GDP per capita of 1400$ is simply insufficient to escape poverty. However, the GDP growth rate in FY23 as just 1.9% and FY24 was 3.9%. Most recent numbers showed a 10% unemployment rate. For a landlocked, mountainous country with limited financial resources, growth is a challenging endeavour. In FY23, 26.89% of Nepal’s GDP came from money sent to Nepal by expats living in other countries. Nepal ranks among the highest globally in terms of the proportion of remittances to its GDP, indicating a strong dependence on this income source.

Bottom line: In each case, governance deficits and economic fragility are the prime movers. External actors attempt to shape outcomes, but their success is ultimately determined by local factors like government/system legitimacy or trust, institutions, and street-level power.

II. Why uprisings caught: the socio-economic tinder

- Cost-of-living shocks. Post-pandemic inflation and energy spikes strained household budgets across South Asia; countries with low reserves or high fuel dependence suffered acutely.

- Debt & external financing risks. Short-term external debt, weak revenue, and import dependence created sudden-stop dynamics—Sri Lanka is the starkest example.

- Institutional trust gaps. Perceptions of cronyism, corruption, or captured media reduce tolerance for austerity.

- Youth bulges & digital mobilisation. High youth unemployment meets ubiquitous smartphones: grievances scale quickly into street action.

- Polarisation & winner-take-all politics. When the opposition sees no procedural path to power, the street becomes the arena.

These are homegrown drivers; foreign amplification can accelerate them, but cannot substitute for them.

III. The external-influence playbook (and its limits)

The U.S. and allied countries

Tools typically include public diplomacy, sanctions or visa restrictions on rights grounds, civil-society funding, media training, and, in many prominent historical cases, covert action. Washington’s stated aims are stability and democratic norms. US actions show that stability is only for nations aligned with US interests and not for countries that refuse to accept US dominance. There are many prominent and well-known example of US interference. US arming and training Islamist Mujahedin (later became terrorists) to fight the Communist government in Afghanistan in the 1970s. The US is arming and training Neo-Nazi groups like the Azov Battalion to fight Russians in Ukraine.

China

Leans on state-to-state finance (infrastructure loans, swap lines), elite ties, party-to-party exchanges, and commercial control of strategic assets (ports, power). Its model creates leverage through debt renegotiations and physical footholds—but also breeds local backlash if projects are opaque or land-intensive.

Gulf states, Europe, others

Provide remittances, energy credit, and investment; can nudge elites through money flows and diaspora channels. Influence is real but rarely decisive without local traction.

Limits that all outsiders face:

- Legitimacy, foreign patrons can’t manufacture legitimacy to a point. Media articles and the Nobel Peace Prize can create a good image, but these quickly erode without sufficient on-the-ground backing.

- Information friction: open societies are noisy; narratives face contestation.

- Blowback: visible meddling produces nationalist backlash and policy reversal.

IV. What history shows: documented foreign interventions elsewhere

To separate rumor from record, look at cases with declassified material:

- Iran (1953): MI6–CIA covert action (Operation Ajax) helped topple Mossadegh—now widely documented.

- Guatemala (1954): CIA-backed operation against Árbenz.

- Congo (1960–61): foreign involvement amid Cold War turmoil; archival evidence shows extensive meddling.

- Chile (1973): U.S. destabilisation efforts against Allende; military coup followed.

- Indonesia (1965): still debated; Cold War context and mass violence shaped regime change.

These precedents prove that external orchestration has happened, especially in the early Cold War. But they also show risks: long-term instability, anti-U.S. sentiment, and reputational costs. Since the 1990s, overt regime-change operations have become politically costly; influence now tends to be economic, informational, and legal-diplomatic, not tanks at palaces.

V. Were recent South Asian crises “orchestrated”? A cautious assessment

- Sri Lanka 2022: The immediate trigger was domestic fiscal collapse and fuel shortages. The fiscal collapse was largely the result of the government’s decision to promote organic farming and the downturn in the tourism sector due to COVID-19. While unrest was not of direct foreign origin, Srilanka’s high adherence to economic models championed by the Western Leftist organisations and such as the human development model coupled with the debt they took on as part of Chinese development projects, played a major role in how the economic crisis came about.

- Pakistan’s ongoing churn: Competing narratives abound (including claims of U.S. meddling and counter-claims of domestic power struggles). Independent analysis points to civil–military dynamics and economic distress as primary; outside powers, including both the US and China have influenced outcomes.

- Bangladesh protests: When a man living in the US, with no political backing, is made de facto Prime Minister after a coup, this raises eyebrows. The complete lack of political clout of the current de facto PM of Bangladesh can be seen from the fact that his official title is Chief Advisor to the Government of Bangladesh. The only issue with that title is that there is no government of Bangladesh to advise. The ousted Prime Minister Shiek Hasina herself blamed the USA for unrest in the country. She claimed the USA was trying to create a base in the region to oppose China, and she was being ousted for not agreeing. The protests in Bangladesh were led by Leftist organisations, NGOs, and Jamat-e-Islami. The visit of American businessman and Globalist George Soros’s son to Bangladesh, who went on to declare the overthrow of an elected government as a great victory even as riots ravaged Bangladesh, the Military was on the streets enforcing martial law with deadly force, and the economy collapsed, further gives weight to the claim of US involvement.

- Nepal: Coalition instability is overwhelmingly endogenous; while foreign influence exists, it is too early to tell which way the wind is blowing in Nepal or who the real players are who made this coup happen.

Conclusion: Definitive proof of intelligence operations is always hard to come by, but when the fates of entire nations and millions of human beings are at stake, erring on the side of caution is always the better choice.

VI. Why India has been hard to destabilise (and likely will remain so)

- Scale and federal depth. India’s 1.4-billion-person polity, independent Election Commission, and multi-level federalism diffuse power and create shock absorbers.

- Institutional redundancy. Courts, CAG, RBI, competition authorities, and a robust audit culture complicate capture—no single lever flips the system.

- Competitive politics with high participation. Vote participation is almost always in excess of 70%; state elections routinely change governments, change through ballots, not barricades.

- Economic size and diversification. A 4T economy with large domestic demand is less hostage to a single lender or commodity price.

- Security and counter-influence capacity. India’s intelligence and cyber capabilities, plus DPI (Digital Public Infrastructure) that reduces information vacums, limit foreign narrative dominance.

- Plural civil society and free media space (contentious, imperfect, but vibrant). Multiple national narratives compete—monopolising consent from abroad is hard.

- Diaspora and external partnerships. A globally embedded, high-skill diaspora and strategic partnerships (U.S., EU, Quad, Gulf, Japan, Russia) give India multiple external hedges, reducing vulnerability to any single pressure center.

- Large Online Presence: Indians are the single largest population on the internet today, and it hard to drown out their voice. While Indians may have gripes here and there, they are overall happy about the direction of their country. Today’s India is the fastest-growing global economy, and the majority of Indians are proud of their nation’s achievements.

- Historical Correction: Having endured a 1000 years of foreign invasions and come through horrific atrocities, Indians are very sensitive to foreign interference. Indians tend to close ranks when there is even a hint of interference in our national matters.

Result: while India faces information warfare, economic pressure, and proxy messaging, the system’s redundancy and legitimacy channels raise the bar for any successful foreign regime-change project.

VII. The U.S., “deep state”, and India

The US has supported Pakistan economically and militarily for decades. The height of which was the USA sending aircraft carrier battle groups to prevent India from stopping Pakistan’s genocide in what was then East Pakistan in 1971. The USA has been historically accused of killing the father of the Indian space program and nuclear program. USA also tried to prevent India from developing a space launch vehicle with a cryogenic engine in 1990s. In the 2000s, a senior Indian IB officer was discovered as a ,US spy, and he fled to US shortly before he was about to be arrested. The US is giving refuge and free rein to anti-India Khalistani terrorists like Gurucharan Singh Pannu and organisations like Sikhs for Justice even today, despite claiming to be a friend of India. American billionaire left-wing political activist George Soros openly declared his intent to oust Modi when speaking at the World Economic Forum, Davos. He also pledged significant sums of money to that cause. Recent political tussels in the US between the Trump administration and Soros have resulted in the divulging of US government funding being given to George Soros for his so-called “humanitarian works.” During the Biden administration, US diplomats went and met many separatist figures and opposition politicians within India and reportedly even publicly expressed their desire to oust Modi. The India-US relationship was so bad that the Biden administration didn’t even appoint an ambassador to India for the first 3 years of his 4-year term. Currently, with this latest tariff issue, former US NSA and current Advisor Peter Navarro has even gone so far as to call the Russia-Ukraine war Modi’s war based on India’s purchases of Russian. Needless to say, the claim is absurd as both China, Europe, and Turkey buy more oil and gas from Russia than India. Ironically, as Navarro was busy crediting India as the force behind the Russian war machine, India emerged as the largest supplier of diesel to Ukraine for July 2025.

VIII. China’s political-economic leverage—and its ceiling

Beijing’s influence rises where financing gaps are large and elites seek fast infrastructure. But the “debt-for-leverage” model faces popular backlash (Sri Lanka’s Hambantota lease became a political liability) and security suspicion in India. In India specifically, capital controls, investment screening, and security review around telecom, ports, and power cap strategic entry points. China’s information operations exist but cannot manufacture legitimacy in a noisy, federal democracy with competing media ecosystems.

IX. What India should do next (policy playbook)

Short term

- Crisis insurance for neighbours: targeted credit lines, fuel and food support, and swap arrangements, reduce the opportunity cost of choosing India.

- Factual counter-narratives: multilingual media, diaspora engagement, and open data on development assistance to inoculate against disinformation.

- Help foster civil society organisations that promote democratic values, discourse, and peaceful change

Medium term

- Connectivity that delivers: BBIN corridors, coastal shipping, and grid interconnections that tie neighbours to Indian growth.

- Transparent financing standards: publish terms, environmental safeguards, and community benefits; set the region’s gold standard for infrastructure governance.

Long term

- Human-security diplomacy: scholarships, health networks, and disaster-response cooperation build publics, not just elites.

- Resilient democracy at home: credible institutions are the ultimate counter-influence strategy; they turn foreign narratives into noise.

X. A note on boycotts, xenophobia, and the Indian diaspora

Economic coercion and xenophobic rhetoric anywhere in the world create backlash risks: consumer boycotts, talent relocation, and supply-chain re-routing. Indian immigrants have been central to American tech and research leadership; any uptick in racism or visa uncertainty erodes goodwill and pushes high-skill flows toward alternative hubs. In another 20 years

Conclusion

South Asia’s instability is foreign-influenced and in some cases even foreign-driven, but it is still the result of domestic economic fragility and governance gaps. Foreign actors can provide financing and even the narratives, but if it is disconnected from reality, it will strengthen the nation. India, by contrast, has proved structurally resilient because of its scale, federal ballast, competitive politics, diversified economy, and maturing state capacity. That does not make India immune to pressure or disinformation—but it does make externally engineered regime change highly implausible.

The practical task for New Delhi is to act as the net security provider for the neighbourhood. A stable neighbourhood will help in India’s growth story, and India’s competitors will try to prevent it. Secure partners against shocks, connect markets, set standards, and keep India’s own democratic and economic flywheels turning. In geopolitics, resilience beats conspiracy—and execution beats intention.